The story of Greenleaf’s Widow, the Princess Nai Tai Tai

Karen Fox

EDITORS NOTE: My friend Karen Fox, a long-time journalist and editor, recently came across an article she wrote more than 50 years ago about Amelia Parker, a woman known to pool history fans as the famous “Princess Nai Tai Tai.” Amelia Parker was not a pool player, but rather a vaudeville star who was married to pool legend Ralph Greenleaf during the height of his Jazz Age fame. Karen interviewed Parker extensively and then submitted her article to Bowlers Journal and Billiard Revue, the precursor of today’s Billiards Digest. It ran in the March 1966 edition under the headline “The First Lady of American Pool.” But the article has not been seen since. Not until now, anyway.

There’s a lot to love about this piece. The writing is great. The details are fascinating. But beyond that, Karen’s piece feels like an open telephone line to the foggy past, like a Ouija board connection to Vaudeville and the Jazz Age. Amelia Ruth Parker was already a famous stage figure when she married Greenleaf in 1925. She was a big personality in her own right, and this article focuses more on her than on Greenleaf himself. In her interviews with Karen, Amelia Parker recounts details of her life before meeting Greenleaf, of her colorful Vaudeville life and her dressmaking days after Greenleaf’s death. “I had many conversations and several interviews with Amelia — at her dress shop and at her home over a few years time,” recalls Karen. “Amelia accompanied me on the train for the publicity breakfast at McGirr’s pool room in Manhattan (for the debut of Karen’s late husband’s book on Minnesota Fats). She had a good time — though she always looked down her nose at Fats for being a hustler and not a gentleman’s billiard player.”

Karen has slightly re-edited her piece and we reprint it here with permission from Billiards Digest. This is the first time this article has appeared anywhere since 1966, and it won’t be found anywhere online except here, at PoolHistory.com.

— R.A. Dyer

By Karen Fox

Vaudeville star Amelia Parker and celebrated billiard champion Ralph Greenleaf met in Philadelphia, and it is there — in the City of Brotherly Love, that Amelia put down deep roots until the end of her days.

Candid photos of Amelia Parker in 1966, more than a quarter century after Greenleaf’s death.

I met Amelia in 1964. Newly married, my husband Tom Fox, writer for the Philadelphia Daily News and contributor to Sports Illustrated, and I lived in a charming 3rd and 4th floor apartment, above an antique shop at 112 South 20th Street. Tom was finishing the book he was writing about pool hustler Minnesota Fats aka New York Fats – The Bank Shot and Other Great Robberies. He, too, was writing profiles of pool hustlers and champions for Mort Luby’s Billiard Revue headquartered in Chicago.

Our apartment was between Chestnut and Walnut Streets, off Rittenhouse Square, in Center City. We walked everywhere – to work, church, the grocery and theater. Almost daily I walked past the handsome Victorian era townhouses, now with shops on the first floors, in the 20 hundred block of Walnut. There were photography studios, oriental rug stores, delicatessens, book stores, a couple coffee houses and small bars. And, there was a wide glass store front—bare, except for white silk in deep folds gracefully draping the window. In the corner, strategically placed, was a tall oriental vase holding long- stemmed apple blossoms. The small elegant gold- lettered sign read “Amelia Gowns – One of a Kind Accents.”

These photos are by Mort Luby, former publisher of Bowlers Journal and Billiard Revue.

It is there I found Amelia Parker Greenleaf. I had been tipped off Ralph Greenleaf’s widow was a dress designer in Philadelphia by Earl Newby, a retired police officer, who had a walk-down pool room at 11th and Chestnut, and an obsession for details about the life of Ralph Greenleaf.

An amateur seamstress who made most of my own clothes at the time, I was amazed, transfixed and inspired by Amelia, and spent hours with her – mostly listening and sometimes helping her, in her custom dress shop.

In 1966, I wrote a story about her for the Billiard Revue. Mort Luby, the publisher, in town for a visit, shot some wonderful images of Amelia showing her exuberant self. Here is the story.

Princess Nai Tai Tai’s marriage to Ralph Greenleaf.

THE FIRST LADY OF POOL – AMELIA GREENLEAF

It was three o’clock in the morning and downtown Philadelphia was deserted when two women, carrying a bulky figure draped in muslin, stepped from a doorway at 2018 Walnut Street. A policeman in a red patrol car braked for a second look, but drove on. A beatnik stepped up from a basement coffee shop, chuckled, and said he was going to call Scotland Yard. Amelia Greenleaf was so tickled she dropped her end of the size 18 dress form, and had a hearty laugh. Amelia had loaned me the dress form, and we were carrying it two blocks to my apartment after working into the night finishing a wedding gown for one of her best customers, the daughter of the most prominent haberdasher in Philadelphia.

Amelia Greenleaf is a high fashion designer. Her clientele list is small, but prestigious, and carefully guarded by her customers who don’t wish to share where they acquire their straight- lined, perfectly fitted garments in finest fabric.

Amelia is as well, a blithe spirit, impetuous and lovable, but never allows her current or previous stereotypes bridle her behavior. “Dahling,” she says, in a deep throaty theatrical voice, “I enjoy being me, and what do you know – most people like me that way.” Her long gray hair is knotted carelessly in a chignon atop her head. She wears shapeless shifts and sandals, yet she fascinates physically. Her austere, handsome features reflect her Anglo-Chinese ancestry. When she talks, and she talks a lot, her hands punctuate her words, the many jade and silver bracelets on her arms tinkle like chimes.

When she works, her hands are her tools of fabric art.

At 72, she has nary a thought of retirement. She rides public transit six miles to and from her shop to her rowhouse, in Southwest Philadelphia. She often works around the clock, napping a few hours in a wicker chair over three or four days, when on deadline finishing couture for a wedding or debutante’s coming out. “God,” she says, “created man to create, and I create. I create gorgeous gowns. It’s my work, my life.”

As dawn broke this particular spring morning over William Penn atop Philadelphia City Hall, Amelia noted day break is her favorite time. It’s the only time, she says, when she looks back to her life as Mrs. Ralph Greenleaf, wife of the glamorous all- time champion of pocket billiards. Those years were spent at Allinger’s and McGirr’s in New York, Bensinger’s in Chicago, Allen’s in Kansas City, Cochran’s in San Francisco and thousands of other lesser known pool halls. Newspaper headlines chronicled their stardom: Greenleaf Wins Title Again…Greenleafs Wintering in Havana…The Greenleafs Return to Stage.

GREENLEAF DEAD AT 50

Then, in March, 1950 came the Page One news: Greenleaf Dead at 50. And, Amelia vanished from public view. For 25 years, she had lived in a goldfish bowl as the First Lady of Billiards.

She had been a headliner herself, starring as Princess Nai-Tai-Tai, the Oriental Nightengale of Vaudeville.

It was on this same Walnut Street in Philadelphia where Amelia first met Ralph Greenleaf. Both names were featured on theater marques. She was starring at the old Globe Theater at 13th and Market Streets, a few doors down from Allinger’s billiard room where Greenleaf was performing exhibitions. He enjoyed relaxing to music and took in the matinee performance at the Globe.

He was captivated and curious about Prince Nai-Tai-Tai’s voice and beauty. She was known for her whispery singing – “soft, but I could  be heard at the box office,” she says. “Ralph arranged for a very proper meeting,” says Amelia. “He took me to dinner at a little Italian restaurant on Walnut Street. He was handsome, polite, interesting and interested in me. Honestly, he swept me off my feet, darling.” They were married in 1925, but secretly. When word leaked out, headlines splashed across the globe.

be heard at the box office,” she says. “Ralph arranged for a very proper meeting,” says Amelia. “He took me to dinner at a little Italian restaurant on Walnut Street. He was handsome, polite, interesting and interested in me. Honestly, he swept me off my feet, darling.” They were married in 1925, but secretly. When word leaked out, headlines splashed across the globe.

Amelia gave up singing, and Greenleaf joined the vaudeville circuit. The two performed together as “Ralph Greenleaf, the Aristocrat of Billiards, Assisted by Princess Nai-Tai-Tai. “We opened the act in Philadelphia,” says Amelia, “at the old B. F. Keith House at 1120 Chestnut, and we shared the bill with Ethel – that is Ethel, as in Barrymore!” The Greenleafs were driving a Stutz Bearcat and earning $2,000 a week, tax free – then sufficient to buy a home or car. “Ah, the 20s,” she remembers, “the most wonderful days ever. Glamour and good times – even the air was different.”

Sports figures were idol worshipped. Ralph Greenleaf, the billiard champion, enjoyed equal sports page headlines with Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Red Grange, Bill Tilden, Gene Tunney. Between vaudeville bookings the Greenleafs vacationed in Havana and California.

“THE DEPRESSION CHANGED ALL THAT”

“The Depression changed all that,” says Amelia. “When the banks died, so did vaudeville and billiards.

For a time in the 30s, the Greenleafs managed Willie Hoppe’s billiard room in the Roseland Building in New York City. Greenleaf’s green cloth finesse and championship stardom attracted celebrities. “There were a young Milton Berle and then relatively unknown singers Bing Crosby and his brother Bob, and writer Damon Runyon (author of Guys and Dolls) who always had an ear bent for good dialogue.”

As the Depression wore on, and the need for cash became critical, Greenleaf took to the road again. “It was just like returning to vaudeville,” says Amelia. “Ralph played exhibitions in every part of the country. I have traveled every inch of this land, and I have been in more rinky- dink towns than a Fuller Brush salesman.” She is remembered sitting on the rim of crowds, petting her little Chihuahua, attracting attention with her handsome regal presence.

On the road, Amelia says she grew weary of smoke-filled pool halls and the rehashing of games of who is the greatest. She routinely retreated to the hotel and hunted down a sewing machine. “I would ring up Singer’s and request they deliver a sewing machine. I’d run out and buy yards of finest fabric – pale yellow, lavender, pink and blue, get down on the floor and cut out half a dozen shirts for Ralph. My Ralph loved the shirts. Important people would say, ‘Ralph, that is the most beautiful shirt, who is your tailor?’ – He’d say, ‘My wife,’ and of course, no one believed it.’”

Amelia enjoys telling how she became a couturier in the early days of her life.

Amelia Ruth Parker was born in Kingtzekwan (prounounced Gin-sa-gwen) on the banks of the Yangtze River in the north central China Province of Honan. “Ah, Kingtzekwan, the City of the Golden Thorn, so beautiful, so graceful, so leisurely. There was a moat all around the city, and a wall that went straight up with ramparts where they shot bows and arrows at the brigands. And outside, there was this hedge with orange-like fruit on it, and in the fall, the whole hedge would turn brilliant gold. Ah, darling, it was so tranquil, so charming.

“It was in the valley, you see, below the mountains – Huashan, that was Monkey Mountain, and Watushan, that was the Mountain of the Rain God. And there were temples on the mountains where the Buddhists went to worship.

“There was great excitement during a drought. I remember all of the citizens would put on shackles and make pilgrimages to the summit of Rain Mountain. What a deafening din they made with all their crazy gongs and whistles and singing and chanting. But don’t you know,” she whispers, “the rains did come in torrents, in downpours, my darling.”

It was there in late 19th Century China that Amelia played with her brothers and sisters in oriental gardens surrounding their expansive pagoda. The Parkers numbered nine. Amelia’s father, George Parker, was “a secret agent for the British government who traveled without portfolio.

ENGLISH AND ARISTOCRATIC

He was English and aristocratic,” says Amelia, “and if I might say so, an early version of James Bond. He was a Freeman of London who traced his ancestry to Richard the Lion-Hearted.

He traveled the world over. He was on a clandestine assignment for the British government in Kingtzekwan when he met and fell in love with Mien-Tse-Tai, a Chinese princess of royal lineage. Their storybook romance lasted for more than half a century, and produced me and six other children.”

George Parker did not return to London with his family because his wife could not tolerate the damp polluted air. “She was such a delicate little creature, my mother,” says Amelia. “I remember Father saying Mother looked like an apple blossom. He was very protective of her.

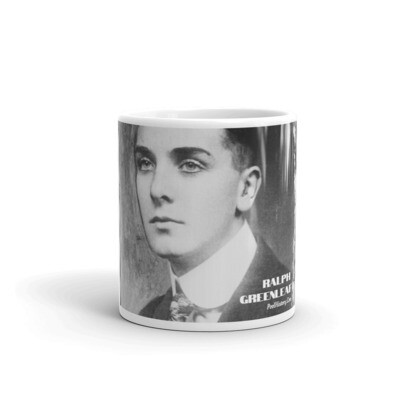

Ralph Greenleaf coffee mugs and more pool history merchandise at the Pool History store.

“That brings to mind,” she says, “of his concern over the Boxer Rebellion. Yes, I remember the Boxer Rebellion! I was six years old and my eldest sister Hannah was home from school in England, and trying to tutor me in math – as all six- year- old subjects to her Majesty Queen Victoria must go to school. So, she’s teaching me how twice one are two under Father’s apple tree in the garden when all of the sudden, a runner comes bounding in all the way from Peking. He’s come to warn us we must leave this very minute – that all foreigners are going to be murdered –that the Boxers are coming! (The Boxers were a force to be reckoned with — a secret political protest group of mostly peasants who took to violence demanding all foreigners be banished from the country.)

“We scurry and pack up. By afternoon we are sailing down the river toward Shanghai. That night we could hear the Boxers running up the banks, pillaging as they went. That was the most narrow escape in this world. Right today I would be dead,” she whispers.

The Parkers returned home a year later. “Mother hated Shanghai. She couldn’t breathe.” They expected their pagoda and treasures to have been destroyed, “but the citizens saved everything, even the gardens, our porcelain and ivory, as they loved and protected Father.”

Now past her sixth year, it was time for Amelia to leave home. British rules required she attend school in England. “It broke Mother’s heart, but I was an adventure- some little rascal. I got on the boat, and like Father, I thought I was going on some grand secret mission.”

Amelia attended Finnart School in Newquay “in the Duchesse of Cornwall, on the southern tip of England, a few miles from Lands End. It was a finishing school teaching the culture and traditions of the English aristocracy.

“Prince Albert who was later King George VI and the Duke of Cornwall whose father was the Prince of Wales visited our school as did Queen Alexandra. She was magnificent, looked like she was carved from marble.”

Amelia had a classmate whose mother Helen Blake was a dress designer and seamstress for members of the British diplomatic corps. Fascinated with the feel of rich brocades from the Orient, laces from India and heavy woolens and tweeds from Scotland, Amelia spent as much time as possible in Mrs. Blake’s design studio, sometimes forsaking her homework. Amelia had talent for design, and accuracy at the sewing machine. “We made clothes for the Duchess of Argyle and the wives of the Viceroy of India and the Governor of South Africa, for the opening of Parliament and special ensembles for British holidays. Learning from Mrs. Blake, I was the happiest girl in this world.”

VOYAGE TO CANADA

As a gift when she graduated from school, Samuel Rutherford Parker sent his sister a ticket for a voyage to Canada where he now lived. “It was a lovely day at sea, and I was lounging and watching a theatrical group rehearse Aladdin and the Magic Lamp. Suddenly the director goes mad, has a tantrum. One of the cast had dropped out. He turned around, and saw me gawking, and said, ‘Come here China doll.’

“He said, ‘And, who are you?’ I said, ‘Well, I am Amelia Ruth Pahkah.’ ‘Is that so?’ he said, ‘read these lines.’ I read the lines, and he jumps up and down, yelling, wonderful, wonderful, Aladdin’s magic lamp has sent me a China doll with the most marvelous voice. And, that’s how it started – my life in show business.”

Over a decade Princess Nai-Tai-Tai performed across the country in New York, New Orleans, Terre Haute, Des Moines, Seattle. “You’ll never guess what! I gave my piano player Ted Shapiro to Sophie Tucker. One day Sophie is in tears, her piano player left her, and her show was about to go on. I said, ‘Go ahead, take Ted.’ She did, and he became very famous.”

the late husband of Karen Fox.

Of all the cities on the B.F. Keith vaudeville circuit, Amelia loved Philadelphia best. “It was so proper, so British in architecture and culture. It’s sophisticated, but homey and so livable.”

In the fall of 1965 there was a World Challenge Billiards Match in Philadelphia. Amelia was invited and there was great fanfare since she had not been seen around the sport more than 15 years. She wore a chic white wool ensemble of her own creation for the event. Joe Balsis of Minersville, Pennsylvania was challenging Cowboy Jimmy Moore of Albuquerque, New Mexico. They were competing for the world’s championship, the crown that Ralph Greenleaf wore for 20 years. Amelia says the memories – some bitter, some sweet– were overwhelming. “I couldn’t take it,” she says. “It was simply overwhelming.” She promised to return the second night, but decided not to, and worked in her dress shop instead.

The sewing machine has always been an escape for Amelia and is still today. “I don’t have the feeling that Ralph is gone because I didn’t see him die. I just feel he is out on the road somewhere, that he’ll be popping in any day.”

Greenleaf died at age 50, in 1950, in a waiting room of a Philadelphia hospital. He had been ill for several days, but did not seek medical help because he was preparing for an appearance in New York City the following week. He had suffered from alcoholism for many years.

Amelia Greenleaf died in 1978 at the age of 84. She is buried next to her husband in a cemetery at his native Monmouth, Illinois. They had no children.

Pool History Merch

Help preserve pool history by purchasing a coffee mug, t-shirt or other merch. That's because we re-invest 100 percent of net sales proceeds to pay guest writers and artists. Have an article to pitch? Go to the Guidelines for Guest Writers tab for more info.

Pool History Merch

Help preserve pool history by purchasing a coffee mug, t-shirt or other merch. That's because we re-invest 100 percent of net sales proceeds to pay guest writers and artists. Have an article to pitch? Go to the Guidelines for Guest Writers tab for more info.

Really enjoyed that article big Greenleaf fan

This was a very interesting story of the past. Romantic, mysterious insights to two people’s lives. Vauldville, a sowing mechine, the art of billards, combined with sports heroes, and a secret agent. Now that’s entertainment!